Toxic, radioactive garbage lingers in WWII-era dump at former Donaldson Air Force Base

An old, contaminated landfill at the former Donaldson Air Force Base in Greenville — home to nearly 100 companies in what is now a 2,600-acre industrial park — poses a high risk to human health, according to data compiled by the investigative group ProPublica.

Donaldson is among thousands of former military installations nationwide with lingering pollution issues, according to ProPublica. The group’s data drew from the U.S. Department of Defense’s Environmental Restoration Program, which lists 61 current or former military installations in South Carolina that need environmental cleanup.

Of the 61 South Carolina sites, 11 are in the Upstate. Of those 11, Donaldson poses the highest risk to human health and the environment.

The Formerly Used Defense Sites (FUDS) program of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers tracks and mitigates pollution at old military installations according to their severity and as money and time allow, said Billy Birdwell, senior public affairs specialist for the corps’ Savannah District.

Work at Donaldson will commence early next year, he said.

“Those with almost no risk go way at the bottom,” Birdwell said. “We rack and stack them and take care of people the best we can.”

Records show that Donaldson is among a handful of installations statewide — six all told and most of them on the coast — that the defense department has deemed high risk, meaning imminent risk to human health, safety and the environment, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Those are:

- Conway Bomb and Gunnery Range (military munitions and explosives), Horry County

- Fort Jackson (the explosive agent RDX has contaminated several residential wells), Richland County

- Parris Island Marine Corps Recruit Depot (spill site), Beaufort County

- Beaufort Marine Corps Air Station (underground storage tanks), Beaufort

- Joint Base Charleston Weapons Station (maintenance yard and landfill), North Charleston

- Donald Air Force Base (contaminated landfill), Greenville

Two South Carolina sites are rated low risk — including the old Isaqueena Lake bombing range outside Clemson — and 12 are medium risk. Another 32 have a “response complete” designation, and the remaining eight haven’t been evaluated.

According to ProPublica, some “completed” sites are simply restricted or fenced off to keep the public away.

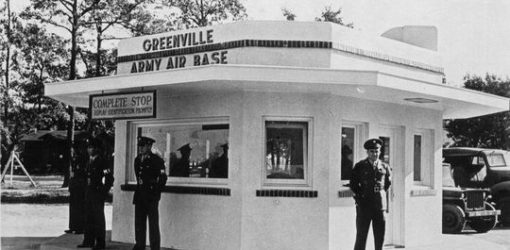

Donaldson operated as a military installation until 1964. During World War II, the airfield operated a skip-bombing school at Isaqueena Lake, nestled at the center of the Clemson Experimental Forest. Bombers practiced hitting targets on the water with dummy bombs, hundreds of which were found at the bottom of the lake when it was drained for environmental work in 1954.

Still, the corps has found the risk of finding any unexploded ordnance under the water low: Most of the practice bombs were stuffed with sand and black powder, according to historical accounts.

More serious is the old landfill at Donaldson Air Force Base, which has been the property of the city and county of Greenville for more than 50 years. Today, a nonprofit called the South Carolina Aviation and Technology Center (SCTAC) manages the site.

The Savannah District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers oversees all cleanup projects for formerly used defense sites (FUDS) in South Carolina and across the Southeast, said Birdwell. Two years ago this work included rendering inert scores of live Civil War-era cannon shot recovered from the Savannah Harbor.

Birdwell said the problems at Donaldson stem from an old dumping site.

Corps scientists have detected trace amounts of hazardous, toxic and radioactive material in the ground water, soil, surface water and sediments around the old dump. These include chromium, mercury, cadmium, the carcinogenic cleaning agent trichloroethylene (TCE), and tetrachloroethylene (PCE), a cancer-causing solvent once used widely in the textile industry.

“We’re not talking about an engineered landfill that you would find in use by a municipality or a commercial operation today,” Birdwell wrote in a email to The News. “This is more of a dump site. During (World War II) we had no environmental science to guide us. We disposed of items in the most convenient way. That meant dumping it, occasionally throwing some dirt on top and moving on with the war effort. We’re fixing that mess now.”

SCTAC’s president and CEO, Jody Bryson, could not be reached for comment, and SCTAC spokeswoman Kara Dullea said she was not aware of the ProPublica report. She declined to comment.

“SCTAC has not received any notice of this but says issues such as this would be the responsibility of the Army Corps of Engineers,” she wrote in an email.

Among the biggest tenants at SCTAC for the past 30 years is Lockheed Martin, which operates an aircraft modification, maintenance, repair and overhaul plant there and has more than 500 employees. With the expected move of F-16 production to the site, another 250 people are expected to come work there.

The ProPublica report said the Donaldson dump site poses a risk to visitors and workers who might be exposed to contaminated soil in the industrial park. It also said anyone wading in nearby streams could be exposed to particles in the water or sediment. Residents of the area also could be exposed through consumption of groundwater.

“We take this seriously, but these are common issues we find at former airfields,” Birdwell said. “TCE and other things — I’ve seen all this before many times at other locations.”

Final action on the Donaldson site will be to make sure that at least two feet of clean top soil covers the entire dormer dump site, Birdwell said. The work will involve heavy equipment and will likely continue through 2021, according to military records.

“We expect to have a contractor there within the first three months of 2018,” Birdwell said.

According to Department of Defense records, the removal of underground storage tanks and other cleanup at Donaldson had already cost the government $21.4 million through July 2016. The remaining work will cost an additional $13.9 million to complete.